-

Arrchitects: Oscar Niemeyer

-

Location: National Congress - Praça dos Três Poderes, Brasilia, Brasília - Federal District, 70160-900, Brazil

-

Project Year: 1960

The concept of a purpose-built capital city in the country's interior dated back to Brazil’s independence from Portugal following the Napoleonic Wars and was even enshrined in Brazil’s first Republican Constitution in 1891. It was not until Niemeyer’s friend and patron Juscelino Kubitschek was elected president in 1956 that progress truly began in earnest.

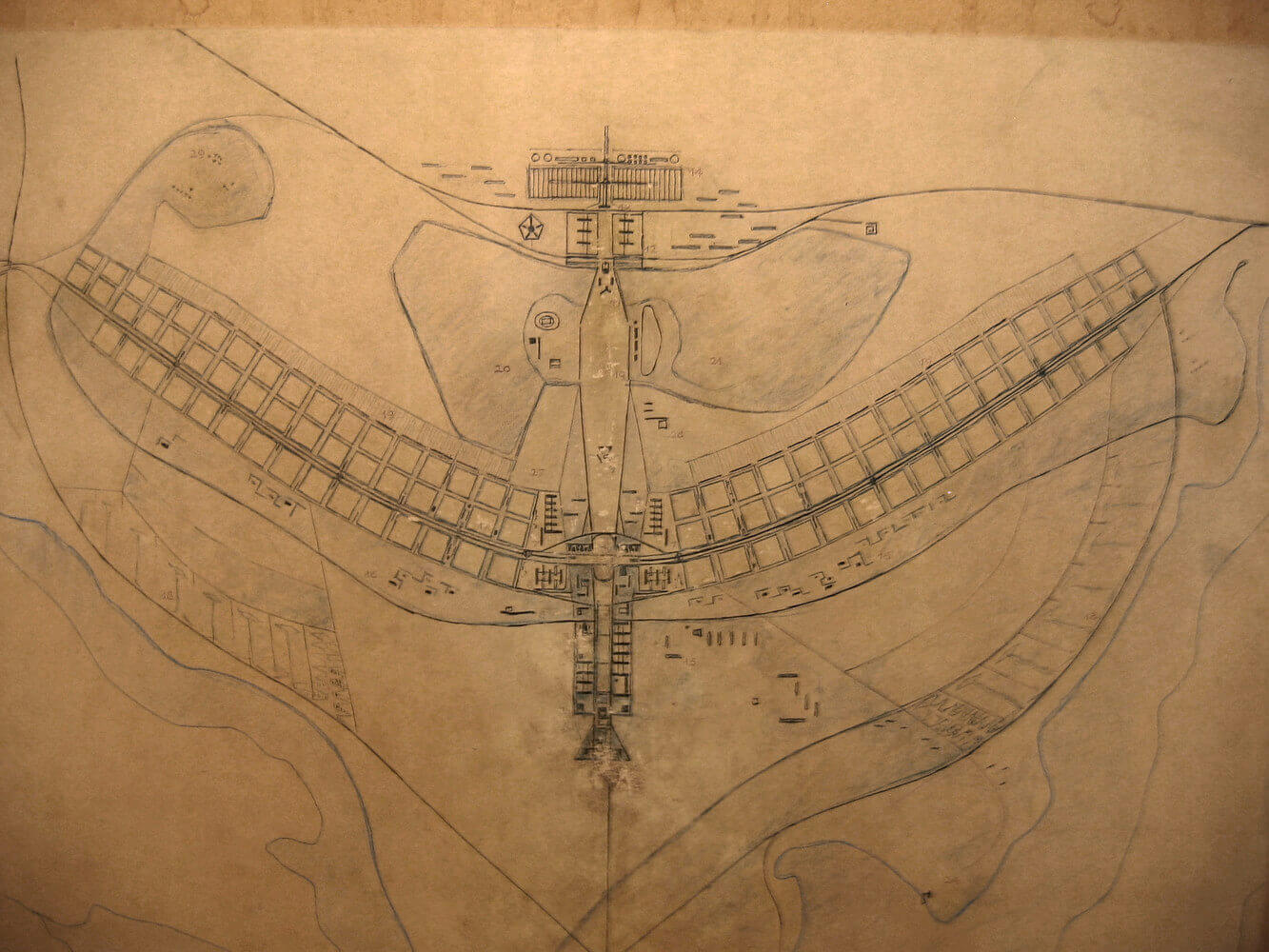

Appointed director of Brasília’s works, “Niemeyer enjoyed a virtual carte blanche over artistic decision making in the creation of the city’s major monuments.” To quiet criticism that Kubitschek had defied a law mandating open competitions for public buildings, the project for the master plan of Brasília was opened to a national competition, but Niemeyer was a member of the jury, and the project was awarded to his mentor Lúcio Costa in 1957. As part of Kubitschek’s “Fifty years of progress in five” plan, the new capital city was designed and constructed with seemingly impossible speed and was inaugurated on April 21, 1960.

Appointed director of Brasília’s works, “Niemeyer enjoyed a virtual carte blanche over artistic decision making in the creation of the city’s major monuments.” To quiet criticism that Kubitschek had defied a law mandating open competitions for public buildings, the project for the master plan of Brasília was opened to a national competition, but Niemeyer was a member of the jury, and the project was awarded to his mentor Lúcio Costa in 1957. As part of Kubitschek’s “Fifty years of progress in five” plan, the new capital city was designed and constructed with seemingly impossible speed and was inaugurated on April 21, 1960.

Perhaps not the most famous or popular of Brasília’s monumental structures (the city seal is a riff on the inverted parabolic arches at the Palácio da Alvorada presidential residence), the National Congress is certainly the most prominent, and the most symbolic of Brasília as the seat of the national government.

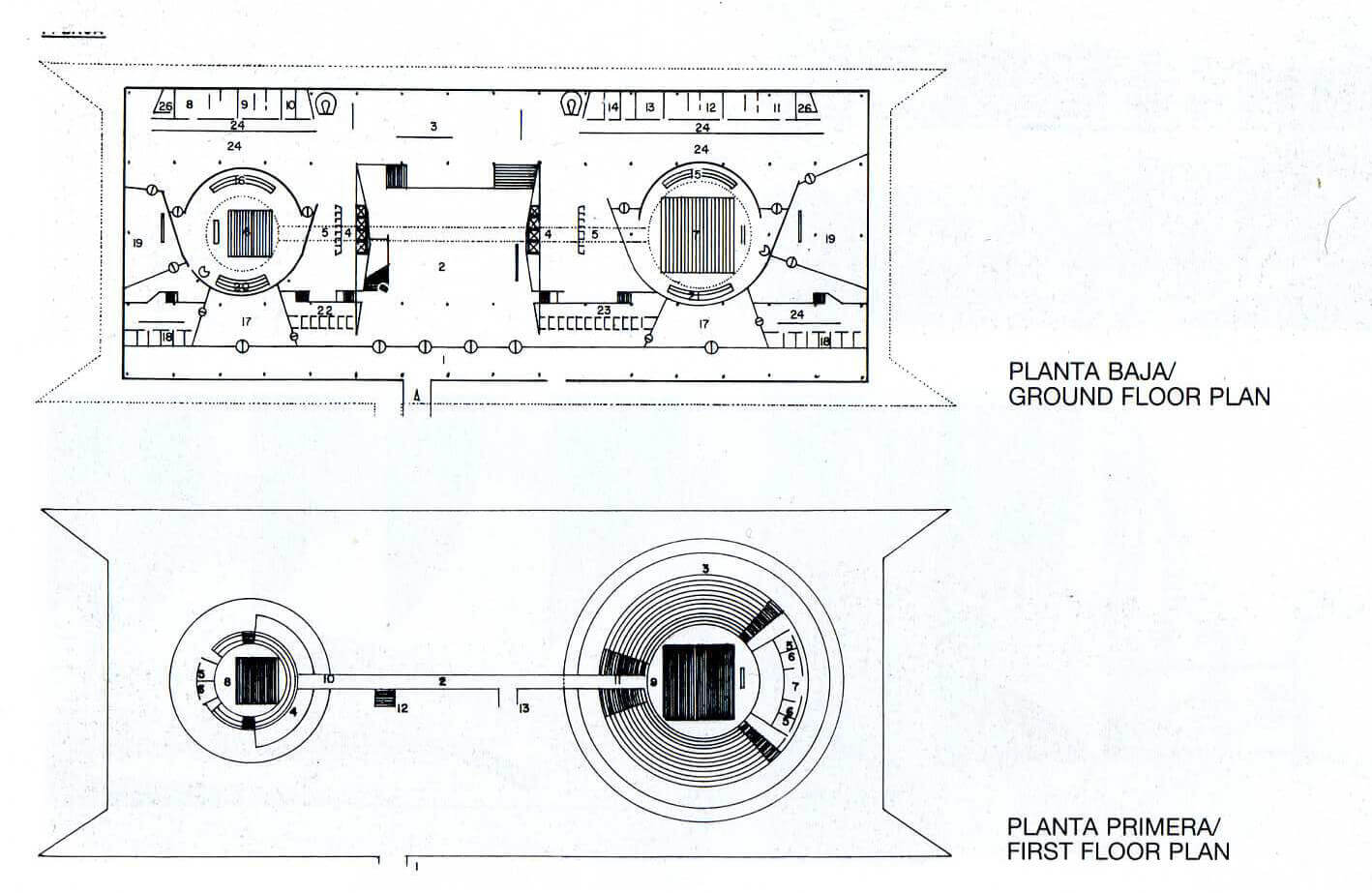

Here Costa’s city plan and Niemeyer’s architecture are joined together: the two wide avenues that mark the Monumental Axis are raised on artificial berms to match the roof level of the two-story plinth of the National Congress building, and triangular segments extend from each corner of the long, flat, overhanging roof to barely touch the edges of the roadways.

Rising above the flat roof, two “cupolas” indicate Brazil’s bicameral legislature's assembly chambers. Previously housed in two separate buildings in Rio de Janeiro, Niemeyer brought the two legislative chambers together in Brasília. Reflective of other seats of power, such as the U.S. Capitol in Washington, DC, or St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the cupola over the Senate chamber takes the shape of a shallow parabolic dome. In contrast, for the larger Chamber of Deputies, Niemeyer inverted the symbolic dome to create a bowl shape.

A long ramp leads from a driveway to the building. Split into two segments, one section of the ramp leads to the entrance of the building, while the other part leads to the plinth's marble-clad roof. Originally intended as a public plaza, the roof has since been closed off due to security concerns.

Beyond the assembly chambers, legislators’ offices and other administrative functions are housed in twin twenty-seven story towers. Set just north of the center, the towers preserve uninterrupted views along the center of the Monumental Axis between the two cupolas and balance the bowl-shaped cupola's visual weight to the south. Though they appear to be necessary slab towers, the buildings are five-sided in the plan, each with two slightly angled façades, coming to a point in the narrow space between the two towers. A three-story bridge also connects the towers on the fourteenth through sixteenth floors. Offices and meeting rooms are located along the outer edges of the towers, while elevators and other service spaces face into the space between the towers.

Ostensibly one part of the Plaza of the Three Powers (the other two being the Planalto Palace, housing the Executive, and the Supreme Federal Tribunal), the National Congress turns its back on the plaza, further distinguishing it from the other government buildings. The grand entry ramp is on the opposite side of the building, and a large reflecting pool separates it from the plaza.

Perceptions of the individual buildings in Brasília are difficult to divorce from the city's opinions as a whole. At the inauguration of Brasília, President Kubitschek was elated, proclaiming the city a national utopia. Other supporters were similarly overzealous. In his book, Brasília, published in 1965, Willy Stäubli raved, “The principles, originality, and perfection of the designs of Lúcio Costa and those of Oscar Niemeyer are so unprecedented and striking that they must be evaluated as a substantial advance in the sphere of modern architecture which established the position of their creators among the great men of modern architecture.”

Many were not so enthusiastic. Critical reception turned negative even before Brasília’s completion, with skeptics describing the city as “Orwellian,” and a “Kafkaesque nightmare.” As Wolf von Eckard described it, “Niemeyer and Costa have realized not just their dream but also Le Corbusier and a generation of planners and architects who followed him… Perhaps, they have demolished the dream by this achievement.” Not even Niemeyer shared Kubitschek’s utopian pronouncements. A lifelong member of Brazil’s Communist Party, Niemeyer fondly remembered the years of Brasília when the laborers and the engineers lived and worked side by side. However, he said, “On the inauguration day, with the President of the Republic, the generals in their full dress uniforms, the deputies dressed to the nines, all state officials and their high-society ladies in their finest jewelry, everything changed. The magic was shattered in a single blow.”

Four years after the inauguration of Brasília, a military coup ousted the government, and the dictatorship soon took comfort in the capital city’s distance from Brazil’s population centers. Niemeyer spent most of the dictatorship period in a self-imposed exile in Paris following harassment from the military government. The association with the dictatorship did not aid Brasília’s reputation, and after the return of democracy in the 1980s, there were efforts to bring the seat of government nearer to the urban centers of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

The passage of time has allowed for more nuance in the views of Brasília. In 1987 Brasília was declared a UNESCO world heritage site, made more significant because it was the first site less than 100 years old, and the first example of the Modernist movement to achieve this distinction. Fernando Lara and Stella Nair suggest that Brasília’s monumental buildings and largely empty plazas are not a failure of public space, but a redefinition of the meaning of open space. In a review of Styliane Philippou’s recent book, Oscar Niemeyer: Curves of Irreverence, Benjamin Schwarz distinguishes between the planning and the architecture, saying, “Today, the city is quite correctly regarded as a colossally wrong turn in urban planning—but Brasília, paradoxically, contains some of the most graceful modernist government buildings ever produced.” As Philippou describes in the book, “Brasília has survived, and… today it has a history and a memory and an indigenous generation of citizens who take pride in their ‘green city.’” Perhaps most telling, during a series of nationwide demonstrations that drew hundreds of thousands of Brazilians to the streets to protest rising public transportation fares and the costs of the 2014 FIFA World Cup, protesters in Brasília took to the ramp and the roof plaza of the National Congress, reclaiming the once public space, just as Niemeyer had originally intended it.

Reference: David Douglass-Jaimes. "AD Classics: National Congress / Oscar Niemeyer" 21 Sep 2015. ArchDaily. <https://www.archdaily.com/773568/ad-classics-national-congress-oscar-niemeyer> ISSN 0719-8884